Models of Attention

Several models attempt to explain how attention works:

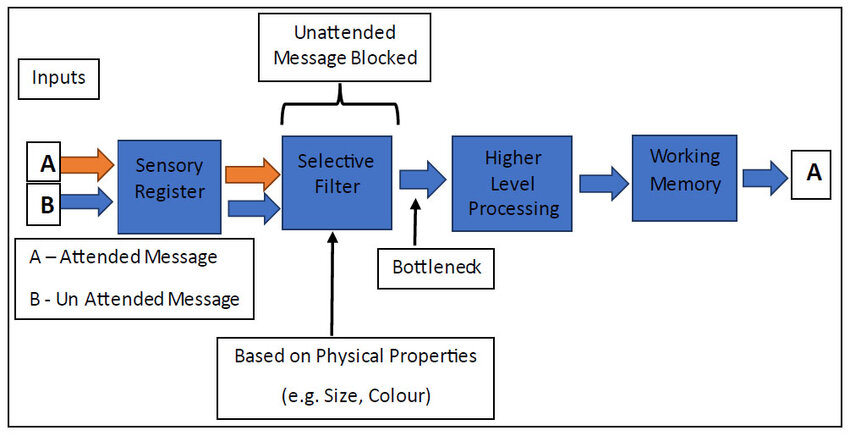

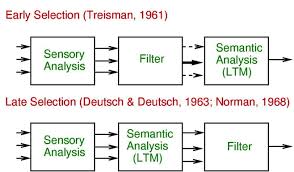

- Filter Model (Broadbent, 1958): This model suggests that information from different sensory channels (e.g., vision, audition) is filtered early in processing. Only the attended channel passes through the filter, while unattended stimuli are completely disregarded. This model is considered an "all-or-nothing" filter.

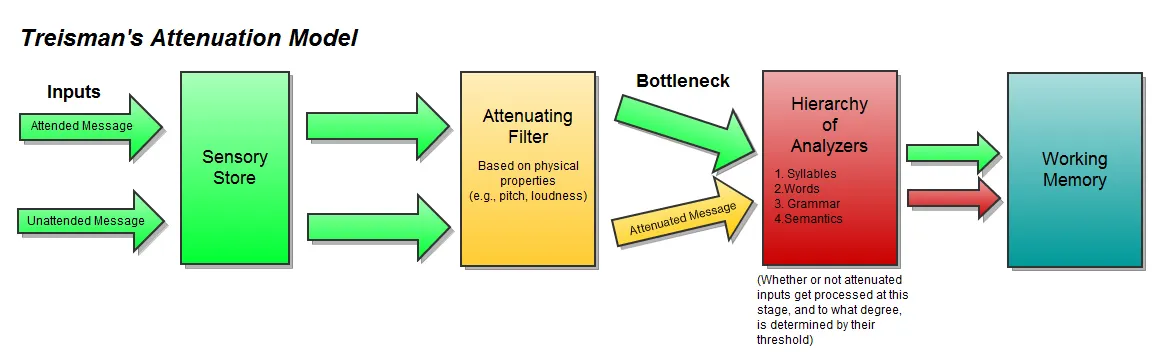

- Attenuator Model (Treisman, 1964): This model proposes a more gradual filtering mechanism than Broadbent's model. Instead of completely blocking unattended information, the attenuator weakens its strength, allowing some information to pass through. This model is still considered an early-selection model but allows for the possibility of unattended information becoming attended if it exceeds a certain threshold.

- Late-Selection Models (Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963; Norman, 1968): These models suggest that all information is fully analyzed for meaning before selection occurs. The filter operates later in the processing stream, selecting information based on both physical properties and meaning. While this model has the advantage of processing all information, it is also more resource-demanding.

- Theory of Perceptual Load (Lavie, 1995, 2000): This theory proposes that the level of selection (early or late) depends on the task's difficulty. Difficult tasks that require a lot of attentional resources lead to early selection to conserve resources, while easy tasks with few attentional demands allow for late selection.

Controlled and Automatic Processing

Cognitive processes can be classified as either controlled or automatic:

- Controlled Processing: This type of processing is limited in capacity, requires attention, is relatively slow and effortful, and operates within our conscious awareness. It is also flexible and can be adapted to changing circumstances. Examples include learning a new skill or solving a complex problem.

- Automatic Processing: This type of processing is unlimited in capacity, does not require attention, is fast and effortless, and occurs outside of conscious awareness. It is often inflexible and difficult to modify once learned. Examples include routine tasks like walking or reading.

Automaticity and Its Implications

Automaticity develops through practice, and Logan's (1988) instance theory suggests that as we practice a task, we shift from using general algorithms to retrieving specific solutions from memory. This transition makes the task faster and more effortless but also less flexible. A classic demonstration of automaticity is the Stroop task, where participants are slower to name the color of ink when the word itself is a different color (e.g., the word "red" printed in blue ink). This interference occurs because reading is an automatic process that interferes with the controlled process of color naming.

While automaticity can be beneficial by freeing up cognitive resources, it can also have drawbacks. For example, the inflexibility of automatic processes can lead to errors in situations that require a change in routine. Examples include driving on the opposite side of the road in a foreign country or accidentally typing an old password instead of a new one.

Understanding attention and its related concepts is essential for comprehending how we perceive and interact with the world. By exploring the different models, factors, and types of processing involved in attention, we can gain insights into the complexities of human cognition.